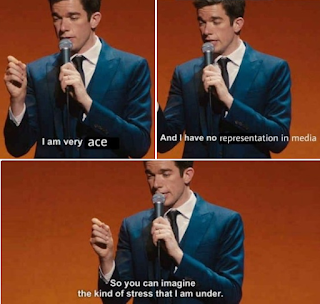

Asexual and Aromantic Humor - The Good, The Bad, and the Funny

|

| Image description: Image not mine, obtained from Google images; this is a perfectly ace spin on John Mulaney's "I am very small and have no money" line. This edit reads, "I am very ace and I have no representation in media, so you can imagine the kind of stress that I am under." It makes me laugh, and so it seems like a perfect image for a post all about humor. |

Many times on this blog, I talk about the tropes and

misrepresentation we see for aspec people of all kinds in media. While it would

seem logical that most of these things would crop up in romance-related media

(and surely they do), in my own analysis, I find the most damaging tropes

are often found in comedy. Because the goal of comedy is to make us laugh, this

is sometimes accomplished by making fun of certain characters, forcing them

into uncomfortable or awkward situations, or making the events that happen to

them seem funny or absurd because of who they are. When those characters are shown to be non-sexual

and/or non-romantic, that becomes especially troublesome, because we are

encouraged to laugh at them and thus not take them or their identity seriously.

Likewise, when a comedy employs aphobic tropes as part of their humor, they

encourage an attitude – whether intentionally or unintentionally – where these

types of discrimination and misrepresentation are seen as silly or no big deal.

Despite the often-jocular nature of these tropes, they are

truly no laughing matter, and they can influence real world attitudes towards

aspec people of all kinds. But humor can also be a powerful tool for good if

wielded correctly. So today, I will be taking a look at humor – both the bad

ways it’s used and the good ways it’s used. Is it possible to use humor

to get better aspec representation? I believe it is. But, like with anything, a

joke needs to be well-crafted in order to do more good than harm. So set aside

the pranks and jokes and silliness for a little and let’s take a serious (but

hopefully still somewhat humorous too) look at how humor can hurt and help and

everything in between on the road to better representation.

-------------------

Humor as Bad

Representation

As a song in the movie musical Singin’ in the Rain once said, “don’t you know everyone wants to laugh?” While this sentiment rings true now more than ever, there is also another universal truth that goes along with that – no one wants to be laughed at. Sure, we’ve all been the subject of well-intentioned teasing or maybe had a harmless prank pulled on us, something we can laugh about with our friends or family in the safety of knowing they mean no harm. But we’ve all also been the subject of laughter that is far less well-intentioned. We’ve all felt the sting of mockery or being belittled or being poked fun at from a place of maliciousness. When it comes to non-sexual and/or non-romantic characters, the latter proves true far more often, showing these characters being laughed at and made the butt of jokes over and over and over again.

Think, for instance, of the countless times on this blog that I’ve mentioned The Big Bang Theory, a comedy which spends a lot of time making fun of the show’s one non-sexual and non-romantic character, Sheldon Cooper. Naturally, not all the show’s jokes are at Sheldon’s expense, and sometimes the jokes that are at his expense are more about humorous situations he finds himself in rather than jokes about his non-sexual and non-romantic nature. However, there are many times where the show allows other characters to mock and belittle Sheldon in ways that are not only supposed to net a laugh, but also encourage the audience to laugh at Sheldon too.

Furthermore, there are many instances where the joke of a

scene is based on Sheldon misunderstanding something sexual, ranging from

double entendre to overt propositions. The humor here is based on the notion of

laughing at Sheldon’s naiveté and he is almost always portrayed in a way that

frames him as being in the wrong. This became especially pronounced when the

character Amy Farrah-Fowler was introduced and when it was decided that Amy

would start to express interest in first a romantic and then a sexual relationship

with Sheldon. There isn’t anything wrong with that – and as I’ve mentioned

before, if it had been portrayed well, we could have had Amy and Sheldon as demisexual and demiromantic representation of sorts. But of course, the show does not usually

portray this with any kind of nuance or respect, and oftentimes Sheldon is

portrayed as somehow being in the wrong for not understanding Amy’s overtures

or not seeming comfortable with the level of intimacy she demands.

Again, there is absolutely nothing wrong with Amy wanting to

be intimate with Sheldon. But there are many things wrong with the way she

chooses to go about trying to get him to be intimate with her, and the ways in

which the show frames these things. It’s not funny to watch a non-sexual

character be harassed, shamed, tricked, and guilted in the attempt to lure them

to have sex with someone, and yet that is exactly what happens. It is likewise

not funny to watch a non-sexual character’s actions be framed as sexual when they

themselves don’t see those actions that way. Two examples of this come to mind

in the same episode.

In an episode in the show's sixth season, Amy is sick and Sheldon takes

care of her. She enjoys the attention so much that, long after she’s well

again, she fakes being ill so that he’ll continue, which leads to a scene where

he decides that rubbing VapoRub on her chest will be helpful. Naturally, Amy

finds this experience extremely titillating, even though that’s not at all what

Sheldon intends. At the end of the episode, he finds out she’s been faking, and

says he believes she should be punished. How does he decide to punish her? I

wouldn’t be able to make this up if I tried – he decides to spank her, which

she likewise finds titillating, of course. Again, it’s not the fact that Amy

enjoys being spanked that presents the issue; the issue comes from, in my

opinion, two things primarily: the first being that Sheldon is not doing these

things to be sexy and thus they are being misconstrued, and the second being

that Sheldon’s lack of awareness about these things is meant to make them

especially funny.

The fact that it wouldn’t dawn on Sheldon that Amy finds

these things arousing strains my credulity quite a bit. I mean, come on, I’m

probably one of the biggest aces you’ll ever encounter in your life and if even

I know it, then even someone as socially unaware as Sheldon should know it, and

that is what makes humor like this so frustrating. The humor of these scenes

only works from having Sheldon be so unaware that it becomes almost farcical.

In order for these jokes to continue to play – which they clearly are, given we

can hear an audience laughing in reply – Sheldon’s lack of sexual awareness has

to become more and more pronounced, as do Amy’s efforts. And in response to

that, we are encouraged to look at Sheldon less and less as someone whose feelings and desires are real, and see him more as an almost satire of

asexuality and aromanticism, encouraging the audience to laugh at these

identities too.

|

| Image description: "Bazinga" is Sheldon Cooper's go-to catchphrase whenever he does something funny - at least something funny by his standards. |

These phenomena happen many, many times with the various non-sexual and/or non-romantic characters I cover on this blog; everyone from Seven of Nine and Data in Star Trek to Emma Pillsbury from Glee have been mocked and belittled in similar fashions. But to illustrate the point of why this has real-world implications, look no further than House episode “Better Half” (which, despite my joke at the beginning of this post, is the opposite of a masterpiece). The episode – as I discuss at length in my “Asexuality is a Medical Condition” post – contains a side plot where Dr. House disproves and cures a couple’s asexuality. That is not something that sounds funny by any stretch of the imagination, and yet there are those who reviewed the episode that found this asexuality side plot exactly that. The AV Club’s review, for example, refers to the storyline as “a goofy enough subplot” and, although they fully acknowledge that the plot was “a quest to disprove asexuality,” they also say it “wasn’t too terrible.”

While this attitude makes me, as an aspec person, bristle, the

reviewers are doing exactly what the episode encourages them to do. “Better

Half’s” asexual storyline is designed to be comedic – by its very nature, it’s

supposed to be making fun of the asexuality and is encouraging its

viewers to do likewise, which is why this review is disappointing but

unsurprising. In a similar manner, humor that frames aspec characters as worthy of

mockery can have real world consequences in that it makes it seem okay to mock real life

aspec people too. Additionally, characters or character types that are aspec-adjacent that are used for “comic relief” can influence real world attitudes

about types of people and how they should be treated. Think of times in media

when we are encouraged to laugh at the “crazy old cat lady,” and think of times

in real life when unmarried people of any kind are treated as “other”

precisely because media teaches us to look down on these people.

Humor as Good

Representation

The bad side of humor can be pretty darn bad. But there are also surprising ways that humor can be used to subtly undermine and even reverse many of the problematic tropes aspec people face. Although these depictions are significantly more rare, there are ways a non-sexual or non-romantic character is able to turn the tables by creating a funny situation where they are not the ones being laughed at. In my own experiences, one of the best examples I can think of is a scene I’ve referenced before in previous posts, featuring Cole from the fantasy video game Dragon Age: Inquisition. Although Cole appears human, his true identity is a spirit of compassion, and as such he has many AroAce tendencies throughout the game. If you’ve read any of my posts about Cole (and the way he both subverts certain tropes and falls victim to others), you’ve heard me reference the good and bad ways this is portrayed and how other characters often react to Cole. These interactions are not always framed well, but one moment between Cole and another character is brilliant precisely because it could have gone horribly and is salvaged by turning the humor of the situation on its head.

In this moment of ambient dialogue, one of the game’s most

sexual characters is expressing his belief that Cole can get “sorted out” by

spending the evening with a prostitute, so he hires him one, expecting that

Cole will be in for a wild evening. This type of assumption about a

non-sexual/non-romantic character is cringeworthy and sadly all too common.

However, in an unexpected moment of reversal, Cole reveals he instead used his

spirit powers to help the woman feel better about a past hurt. The only

reaction that both we as the player and that the other character can really

have is a general sense of realizing this somehow makes perfect sense for Cole

and why did we ever think otherwise. This moment is funny not because we’re

encouraged to mock Cole, but rather we’re encouraged to laugh at the other

character a bit for his mistake, and at ourselves if we too made the mistake of

thinking the outcome would be anything but Cole’s usual shade of quiet

helpfulness.

While I enjoy this moment of banter, as I said, it’s all too

rare – both for Cole himself and in general. I would love to see a time where

moments like this aren’t noteworthy, and where it becomes commonplace for aspec

and aspec-adjacent characters to be allowed to control the joke and not have

the laugh be at their expense. Better still, I’d like to see moments like this

become superfluous, and to see humor not have to rely on the mistakes of

allosexual people, but rather allow aspec people to not have to navigate

these misconceptions at all, or otherwise very rarely. That last dream is quite

a bit further off though, so for now we are left to ask the question of how we

can craft more moments where aspec characters get to make the joke rather than

be the joke. After all, if humor can contribute to bad representation, it makes sense

we can fight fire with fire and also use it to craft good representation,

because humor itself is not inherently problematic as long as it is done well.

Likewise, there is absolutely nothing wrong with portraying

aspec characters as humorous people, jokesters, or having them present in

comedic media. But there is a certain intentionality that should go into that. To

illustrate how easy it can be to fall into certain traps, even within media

with good representation, let’s look for a minute at canon asexual character Todd

Chavez from the Netflix series BoJack Horseman. In the post I did featuring

Todd, I referenced an article written for TV Guide by Liz Henges. In it, Henges

points out that, although the show is always careful about how it portrays

Todd’s identity, the way Todd himself is depicted is often anything but serious.

“It’s hard to watch a show that’s doing so much for ace representation to do so

little with its ace character,” Henges writes in her article. “I don’t like to

think that I’m someone else’s comic relief on their road to recovery or

destruction.”

This issue with Todd is proof that good representation

requires that characters be multi-dimensional, but it also proves that good

aspec-positive humor is not as easy as just dodging a trope here or avoiding a

stereotype there. In order for humor to be used in a way that does not devalue

aspec people and their journeys, it should give aspec people some level of

control. Of course, if your story does not feature an aspec character or only

features an aspec character in a minor role, this element may not be as

important, and it may indeed be perfectly fine to just focus on avoiding certain tropes

in your humor in order to avoid perpetuating negative stereotypes. However, if

your focus is indeed on trying to use humor as a tool of positive

representation – or if you have a character like Todd who exists as an aspec

person within a comedic world – it becomes more important. So, what do I think

is the best way to get an idea of what’s funny from an aspec perspective? Go

find some aspec humor.

If you’ve ever told a joke to someone who has stared back at

you blankly, or if you’ve laughed along with a comedy while a friend sits in

stone-faced silence, you understand the truth that different people find

different things funny. Thus, aspec humor – just like any type of humor – is

not uniformly the same. Not all aspec people will find the same things funny.

But there are specific forums for aspec humor, memes, and jokes, and these

things are generally funnier to an aspec audience because they appeal to us and

how we see the world. Having different types of humor that different types of

people can relate to is vitally important, and it's also important that even

people who can’t necessarily understand these things on a personal level can

still derive satisfaction or amusement from them.

Above all, there are many ways that characters can be funny or be in funny situations without those jokes being sexual in nature. There are many ways to net a laugh that don’t involve looking down on non-sexual or non-romantic people or making their identities something worthy of mockery. This is why I love comedies such as British radio comedy Cabin Pressure, whose humor is mostly based on silly situations rather than sex or romance, or why I laugh at comedy bits about general life stuff rather than comedy bits about overt sexuality. Looking at examples like those from The Big Bang Theory, it can be easy to get disheartened and to feel like all comedy has to be overly sexualized, leaving aspec people like me out in the cold. But there is indeed a world full of non-sexual and non-romantic humor, and if we make these things more generally accepted comedic staples – rather than tropes and mockery – we may take an unexpected step towards a world that is not only more tolerant, but more funny.

In today’s dark and serious world, nothing can be more

valuable than a laugh. But in the quest for a chuckle or to tell the perfect

joke, we often forget that humor doesn’t exist in a vacuum any more than any

other kind of media does. Rather than rely only on comedy at the expense of

others, I sincerely hope we can get to a place where everyone can be in on the

joke rather than the subject of the joke. The more people that can laugh rather

than be laughed at, the better - and that’s something we can remember every day,

not just on a day like today.

Comments

Post a Comment